Bubbles Spread Like a Zombie Virus

by Noah Smith

The leading academic theory of asset bubbles is that they don’t really exist. When asset prices skyrocket, say mainstream theorists, it might mean that some piece of news makes rational investors realize that fundamental values like corporate earnings are going to be a lot higher than anyone had expected. Or perhaps some condition in the economy might make investors suddenly become much more tolerant of risk. But according to mainstream theory, bubbles are not driven by speculative mania, greed, stupidity, herd behavior or any other sort of psychological or irrational phenomenon. Inflating asset values are the normal, healthy functioning of an efficient market.

Naturally, this view has convinced many people in finance that mainstream theorists are quite out of their minds.

The problem is, mainstream theory has proven devilishly hard to disprove. We can’t really observe how investors in the financial markets form their beliefs. So we can’t tell if their views are right or wrong, or whether they’re investing based on expectations or because of changing risk tolerance. Basically, because we can usually only look at the overall market, we can’t get into the nuts and bolts of how people decide what prices to pay.

But what about the housing market? Housing is different from stocks and bonds in at least two big ways. First, because house purchases are not anonymous, we can observe who buys what. Second, housing markets are local, so we can see what is happening around them, and thus have some sort of idea what information they are receiving. These unique features allow us to know much more about the decision-making process of each buyer than we know about investors in the anonymous national financial markets.

In a new paper, economists Patrick Bayer, Kyle Mangum and James Roberts make great use of these features to study the mid-2000s U.S. housing boom. Their landmark results ought to have a major effect on the debate over asset bubbles.

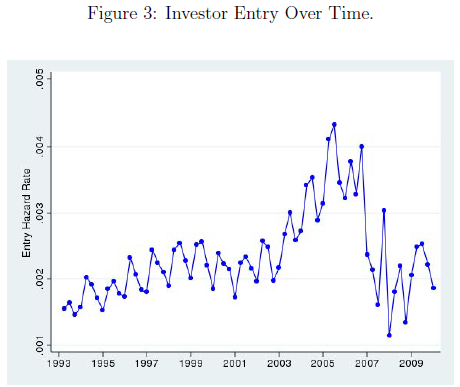

Bayer et al. find that as the market overheated, the frenzy spread like a virus from block to block. They look at the greater Los Angeles area -- a hotbed of bubble activity -- from 1989 through 2012. Since they want to focus on people buying houses as investments (rather than to live in), the authors looked only at people who bought multiple properties, and they tried to exclude primary residences from the sample. They found, unsurprisingly, that the peak years of 2004-2006 saw a huge spike in the number of new investors entering the market. Here is the graph from their paper:

So what was making all these newbie investors start buying houses? The researchers found that one big factor was nearby investment activity. In other words, if lots of people were buying investment properties nearby, it made other people in the area much more likely to buy an investment property. When properties were flipped -- bought and then resold quickly -- it had an even bigger effect in terms of drawing nearby people into the housing market.

This is strong evidence that people were copying their neighbors’ behavior. When people saw other people buying and flipping houses, they started doing it themselves. That stands in stark contrast to the predictions of standard theories of investor behavior, which say that investors only care about the future income that they can earn from their investments. In the case of housing, standard theory says investors just focus on the future rent they can earn on a property, and that all investors have the same information about that future rent. There is absolutely no reason, in standard models, for investors to copy their neighbors’ house-flipping activity. But that is what happened in the bubble.

Even more startlingly, Bayer et al. found that housing investors who mimicked their neighbors ended up performing worse than other investors. That is a good indicator that copycats weren’t learning any new information about the fundamental value of housing.

What were they doing? One possible answer is herd behavior. Economists have studied herding in financial markets, but their theories are generally unwieldy and their results -- until now -- have been inconclusive. Psychological effects, such as greed, or FOMO -- fear of missing out -- are other possibilities. These kinds of effects are regularly cited by financial market participants, but are rarely used in academic finance theory.

The Bayer et al. research may change that. The ability to look into local housing markets, and observe investors and transactions directly, is a bit like the introduction of the microscope in biology -- it opens up a whole new world of evidence. In the past, finance theorists debated back and forth about market data, and what it implied about investor behavior. Now, thanks to the increasing availability of high-quality data, they can look at that behavior directly.

The lesson appears clear: Bubbles exist. Investors aren’t just rational, patient, well-informed, emotionless calculators of risk and return. Now the job is to figure out what really makes them tick.

Courtesy of bloombergview.com