4 Lessons From The South Sea Bubble

Four ways to spot an investing bubble

A study of one of history's first bubbles offers some valuable lessons

by Brett Arends

Some people will tell you the financial markets are efficient, prices are always "correct," and the crowd is "wise." Others will tell you the market is madness, prices are frequently ridiculous, and the crowd is usually downright foolish.

With stocks, junk bonds and other asset classes flying high these days, the topic of "bubbles" is very much of the moment. Many people will tell you high prices reflect high future returns, and to just invest your money and go with the flow. The market knows what it is doing, they say. The market is wise.

Others tell you to duck.

Who is correct?

The people telling you about the wisdom of crowds can typically marshal a lot of theory, mathematical models and Greek letters - "alpha," "beta," and so on - to support their point of view. The most impressive have been able to produce superb charts and mathematical models to show that Wall Street wasn't overvalued even in 1929, and that there was no housing bubble in Miami or Las Vegas back in 2006.

The people telling you about the folly of crowds typically go easy on the theory and mathematical fireworks. They just point to history. A lot of history.

Anyone who wants a basic primer should direct their Internet browser to the free website Gutenberg.org and download a copy of Charles Mackay's "Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds". It was written in the Victorian era, it is free, and it's still current. It contains a classic account of the Dutch Tulipmania, and of the sheer insanity of the stock-market bubble that gripped London in 1720.

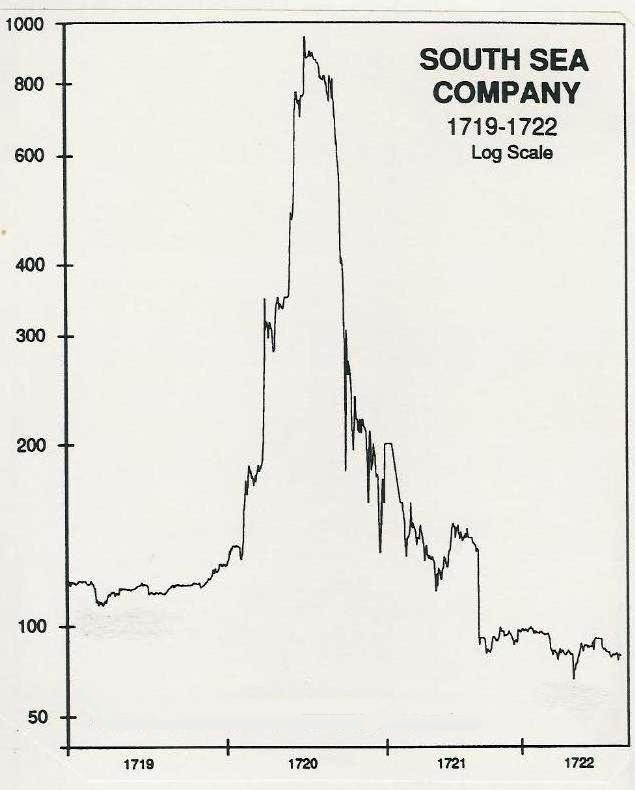

That was the occasion known forevermore as the South Sea Bubble. (It's where we get the word "bubble.") But the mania wasn't just about the stock of the South Sea Company, which skyrocketed about eightfold in the first half of the year and then plunged more than 80% afterward. It was echoed in a mania for all sorts of other stocks - including, most infamously of all, in stock for a new company "For carrying-on an undertaking of great advantage but no-one to know what it is." This was, according to Mackay's account, perhaps the first pure pump-and-dump IPO. The promoter raised a large sum from subscribers to the new company, and then vanished.

Where bubbles come from

What causes bubbles? How do they come about, and how can we recognize them? There is probably no definitive guide, but fascinating new research into the mechanics of the South Sea Bubble has uncovered more information about how it happened.

Giovanni Giusti, at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Charles Noussair at Tilburg University in the Netherlands, and Hans-Joachim Voth at the University of Zurich attempted to recreate the South Sea Bubble in experiments. Subjects participated in financial-trading games designed to simulate the conditions of the South Sea Bubble. The researchers changed different variables in the course of the games to see the relative importance they played .

When I read the paper, four things leapt out at me. All four are useful for any investor trying to hang on to his money.

First, the key factor in the South Sea Bubble was uncertainty. The potential "upside" was unknown, and incredibly hard to estimate.

Here's why. At its heart, the South Sea Company was simply a "shell" company which was buying up British government bonds in debt-for-equity swaps. The "South Sea" moniker was a legacy and was irrelevant to the company's operations or the stock subscriptions.

The South Sea Company had bought up two tranches of British government bonds prior to the great bubble. In early 1720, however, the directors came up with a plan to buy up all the remaining debt. But there was one key difference: They did not set a price in advance. Giusti et al write, "The 1720 scheme was vastly more ambitious - and it contained one crucial difference with the 1719 operation. The South Sea Company proposed to take over the entire remaining national debt (except for the parts held by the Bank of England and the East India Company). Instead of swapping debt for equity at a pre-established price, the company remained vague as to the exchange ratio. This implied that as the stock price appreciated, more debt could be bought for each share."

When the researchers ran their simulations, they found the debt-for-equity swap was the key factor in the South Sea Bubble. Without it, there would have been no bubble. But as this passage reveals, the key issue wasn't simply the debt-for-equity swap: It was the swap at a price to be set later. Thanks to that one characteristic, the sky was the limit for South Sea stock - and no one could tell in advance what the stock was worth. The higher it went, the more bonds they could buy.

Uncertainty is a key factor in bubbles. Professor Lynn Stout, now at Cornell Law School, argues that stocks are more likely to end up overvalued where investors disagree more widely about the true valuation (not least because, if the sky is the limit, it raises the risks of betting against the stock).

Any factor which raises the amount of uncertainty can raise the risk of a bubble. (That can also include, for example, the emergence of new markets or technology.)

The second factor was leverage. In the South Sea Bubble, report the researchers, investors only had to put down the first 10% or 20% of the purchase price in the new subscription. These days we talk about margin debt: But anything which makes it easy to buy more assets than you can really afford, including derivatives, cheap debt, or a central banker walking around the financial district with a bucket, handing out money, would have the same affect.

The third factor was the outsiders buying and the insiders selling. As the stock in the South Sea Company went vertical, Londoners lined up around the block - literally and metaphorically - to participate in this and other IPOs. Meanwhile the original owners of the company were cashing in. Pretty much every bubble since has followed the same pattern. When you see the insiders selling and the outsiders buying, duck.

And there was a fourth factor in the bubble that made me laugh out loud. Giusti and his colleagues have unearthed copies of pamphlets written during the South Sea Bubble proving that the stock was a mania - and which were roundly ignored. These pamphlets weren't just written by a crank, either. Archibald Hutcheson was a member of Parliament. He issued a number of pamphlets, later on during the mania, in which he demonstrated mathematically that people were effectively paying $1,000 in the latest stock subscription for shares only worth $600.

And yet, no one paid him any attention. They carried on buying.

So the fourth characteristic of a bubble is not simply that there are Jeremiahs warning people, but that people pay them absolutely no attention whatsoever.

Is the crowd "rational" and "wise"? You make the call.

Courtesy of MarketWatch