3 Lessons From The Massive VIX Spike Of 2008

3 Lessons From The Massive VIX Spike Of 2008

3 lessons from the stock-market anniversary everyone forgot about

by Mark Hulbert

[BigTrends.com note: The author discusses how the VIX spike of 2008 to above 80 and the subsequent broad market action basically 'blew up' some trading models that were based on VIX reversals in line with a market rebound. However, it must be remembered that in the 20 year history of the VIX, that is the only time it breached above the 40/45 area -- normally it reverses quickly when it reaches 'extreme' highs. So the 2008 VIX and market panic was a once in 20 year type occurrence (actually, more like a once in 40 year one, based on perhaps 1987 and the 1929 market crash as the only other times something similar to this occurred). So-called Black Swans and other events outside the norm of statistical probabilities do occur at times in markets governed by humans, sentiment, and computer models -- but to 'bet' on those events occurring on a regular basis or even to constantly hedge against them has cost many investors a large amount of missed gains over the years.]

This week marks the sixth anniversary of one of the most momentous events in stock market history.

Strangely, I haven't seen any mentions of it, much less serious attempts at drawing the many investment lessons it provides.

I'm referring to the totally unexpected behavior of the CBOE's Volatility Index (VIX) (VXX), in October and November 2008, and the huge damage it caused to trading systems that were based on the VIX.

It was in early October 2008 when the VIX rose to its previous record of 45.74, thereby triggering "buy" signals from virtually all VIX-based market-timing systems. Those systems were based on the contrarian assumption that record-high VIX levels occurred only at or close to market bottoms.

Yet, far from rising, the market kept falling, and the VIX kept rising. By the time the VIX finally hit its closing peak above 80 - on Nov. 20, 2008 - it was nearly double its previous record. And the average stock (as measured by the Wilshire 5000 index) was 34% below where it stood when those VIX-based market-timing systems issued their "buy" signals.

That's devastating enough, but it's only half the story. Following its Nov. 20, 2008, record closing high, the VIX did something that traders found even more inscrutable: Both it and the market continued falling for next three more months. Until then, traders had confidently assumed that the VIX moved inversely with the market.

By the time the market bottomed in the subsequent March, the Wilshire 5000 was 12.1% lower than the already low level at which it stood on Nov. 20. And the VIX was 38% lower.

Here are three investment lessons that I think should be drawn from this sordid experience:

Lesson 1: Make sure your indicators rest on a strong theoretical and empirical foundation.

In the case of VIX-based market-timing systems, this foundation was absent even prior to the 2008 debacle.

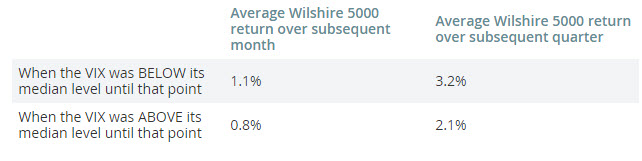

It isn't just Monday-morning quarterbacking for me to point this out, since anyone who bothered to carefully analyze the data prior to 2008 would have detected this. Consider the accompanying table, which reflects the period beginning in 1995 (the first year when there was at least five years of history for the VIX) and ending in 2007 (the year before the 2008 fiasco).

1995 to 2007 VIX Above/Below Median Price & Subsequent WIlshere 5000 Performance Table

[BigTrends.com note: What this above data indicates is that the broad market actually outperforms when the VIX is at a relatively low level. This goes along with our general assertion that the VIX in general has been more of a 'smart money' indicator in recent years -- not necessarily a contrarian 'fade', except for during times of relative extreme peaks/spikes (and possibly extreme lows).]

Lest you think that this data means you should devise a brand new VIX-based market-timing system that is just the reverse of the previous versions (buying when the VIX is below median, in other words), let me hasten to add that the differences shown in this table are not significant at the 95% confidence level that statisticians often use when determining whether a pattern is genuine.

Lesson 2: When testing an indicator, make sure to avoid what statisticians refer to as "look-ahead bias."

We're guilty of this bias when we assume we knew something at a crucial point in the past when, in fact, that something would have been unknowable until a later point in time.

Consider those revised VIX-based market-timing systems today that assume investors should act in certain ways whenever the VIX reaches any level close to its previous closing record of 80.86. The authors of those systems are guilty of "look-ahead bias" when they back-test those systems using data for 2008 because, in 2008, no one could have known the level to which the VIX would eventually rise.

Lesson 3: Past extremes do not represent an inviolable barrier.

This is the most obvious lesson, yet also the most under-appreciated. But we forget it at our peril. Even when an indicator is based on an impeccable statistical and theoretical foundation, it can still fail. So we should never bet all or nothing that it will continue to work.

I was reminded of this by Norman Fosback, who as president of the Institute for Econometric Research in the 1970s and 1980s probably did as much careful statistical work on stock market indicators as anyone in the business. The value of that strong foundation has greatly diminished over time, however, as he wrote a couple of years ago in an email:

"It has been quite disconcerting over the last decade to sit here ... and watch the evolving structure of the market destroy one well-researched market indicator after another - so many years of intense effort now for naught. At least they served us well for a while."

If we remember those lessons, perhaps the trauma of November 2008 will not be entirely in vain.

Courtesy of MarketWatch.com